Solar radio bursts are an indirect signature of accelerated electron beams from the solar atmosphere. These fast electrons generate Langmuir waves as they propagate through a decreasing plasma density and ultimately lead to the bright broadband radio emissions with a characteristic fast frequency drift in dynamic spectra. Density turbulence in the plasma can modulate this process, producing fine structures such as sub-second, narrowband striae and spikes. These fine structures may also present a frequency drift that has been associated with the Langmuir wave group velocity and coronal temperature (Reid et al., 2021, see their equation 2).

As the radio-waves propagate, the turbulence (which is anisotropic with respect to the ambient magnetic field) also leads to scattering effects, causing distortions in their observed position, size, and timing. The broadening of the time profile may also dilute the observed burst drift-rate, which can be particularly significant for narrow bandwidth structures, influencing the interpretation of the driver.

Recent LOFAR observations by Clarkson et al., (2021, 2023) found non-radial, fixed-frequency source motion of radio spikes over time that was attributed to anisotropic scattering in an environment with a non-radial magnetic field such as a coronal loop. In this work, we use an approximation of such a magnetic structure (a dipole) with radio-wave scattering simulations (Kontar et al., 2019) to explain this motion. We further explore the consequences of the scatter-induced reduction of fine structure drift-rates and how their dynamic spectra morphology can vary depending on the emission location in non-radial magnetic fields.

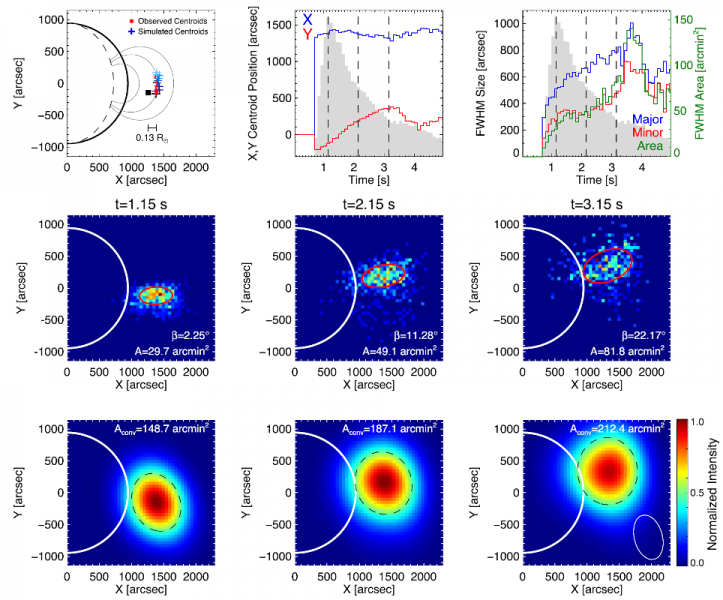

Figure 1. Simulation results for a 35.2 MHz source injected at a heliocentric angle of 50 degrees. (Top Row) Sky-plane centroid motion, X, Y centroid positions, and FWHM size and area, overlaid with the time profile. (Middle row) Scatter images (2D histograms) at different times corresponding to the dashed lines in the upper panels. (Bottom row) Images convolved with a 2D Gaussian mimicking a LOFAR Low Band antenna.

In a radially symmetric magnetic field, anisotropic scattering causes a source shift radially away from the Sun, projected into the sky-plane. In a non-radial magnetic field, the apparent source trajectory (parallel to the local field) and broadening axis (perpendicular to the local field) depends on the emitter’s position within the structure. Figure 1 shows a radio source below the apex of a coronal loop. The source centroids shift vertically in the sky-plane over the FWHM time, matching the fixed frequency, non-radial motion of a LOFAR observed radio spike (Clarkson et al., 2021), both in position and distance. For sources located at the loop apex, photon escape occurs along both directions of the dipole field, preventing a clear centroid trajectory over time. The same mechanism leads to interesting results in certain conditions where a single emission source can produce two distinct components (Figure 2) in regions of strong anisotropy owing to high directivity along the guiding field. As shown in panels (e,f), such source bifurcation may not be observed depending on the instrument resolution. The model further shows that sources emitted along a field parallel to the plasma-frequency surface remain in the strong scattering region for longer, experiencing increased scattering and absorption, which leads to longer durations and fainter sources than those along open field lines.

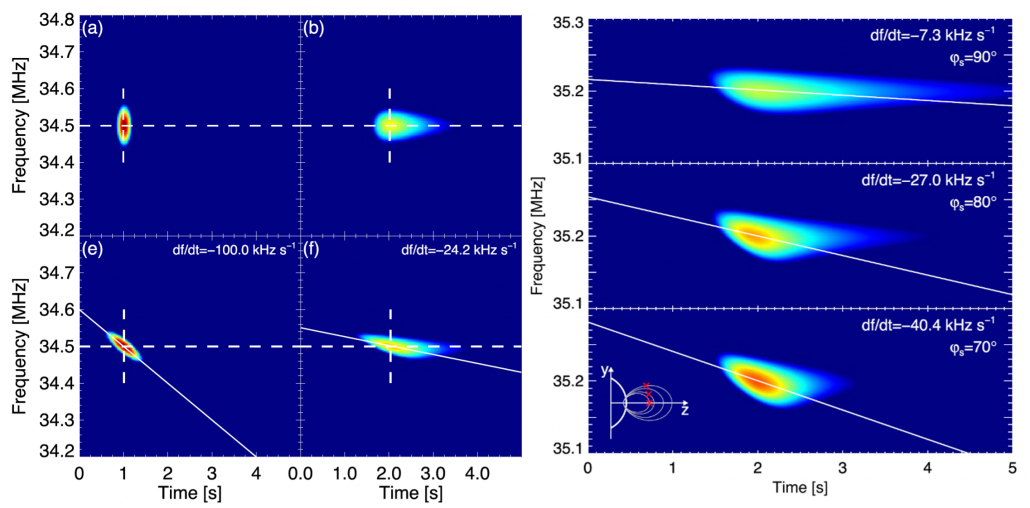

Figure 3 presents initial radio pulses convolved with a scattered time profile for both instantaneous emission, and drifting emission. In both cases, the time profile at each frequency is broadened and delayed. For the drifting case, the frequency drift-rate is diluted, and given the dependence of the time profile on the turbulent conditions and the emitter location in the field structure, the dilution level is also dependent on these conditions; that is, weaker anisotropy and emission near the loop apex produces a stronger drift-rate reduction. The dilution also implies that the observed fine structure drift-rate underestimates the Langmuir wave group velocity and coronal temperature; for example, at 30 MHz, an observed drift-rate of 10-20 kHz s$^{-1}$ implies $T_e\sim(0.3-0.6)$ MK rather than 1-1.5 MK once corrected for scattering.

Figure 3. (Left) Initial radio pulses and the convolution with a scattered time profile. (Right) Initial radio pulses convolved with scattered time profiles from emission sources at different locations in a dipole. (Adapted from Clarkson et al. 2025).

Conclusion

Solar radio burst fine structures present complex dynamics, yet their observed characteristics are further complicated by propagation effects. The inclusion of a dipolar magnetic field in radio-wave scattering simulations highlights how the apparent sources move along the direction of the magnetic field lines, allowing for puzzling non-radial source motion of radio bursts at fixed frequencies to be reproduced, and that anisotropic scattering can produce more than a single source. The observed fine structure drift-rates are diluted depending on the scatter contribution to the time profile. This can vary for sources in different locations in a given magnetic structure and should be accounted for if fine structure drift-rates are used to infer characteristics of the environment and emission process. The results show that both magnetic geometry and anisotropic scattering both play an important role in how we interpret solar radio bursts.

Based on a recent paper by Daniel L. Clarkson and Eduard P. Kontar Magnetic Field Geometry and Anisotropic Scattering Effects on Solar Radio Burst Observations (2025), ApJ, 978, 73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ad969c

References

Clarkson, D. L., Kontar. E. P., Gordovskyy, M. et al. 2021, ApJL, 917, 2, L32

Clarkson, D. L., Kontar. E. P., Vilmer, N. et al. 2023, ApJ, 946, 1, 33

Kontar, E. P., Chen, X., Chrysaphi, N. et al. 2019, ApJ, 884, 2, 122

Reid, H. A. S. and Kontar, E. P. 2021, Nat. Astron., 5, 796-804